橙汁说:版权归原作者Kelly Mcgonigal所有,本文仅作为读文学习使用, 如侵权,请联系搬运工删除。

若出现拼写错误/排版问题或有各种建议,欢迎联系搬运工进行修正。

ONE

I Will, I Won't, I Want: What Willpower Is, and Why It Matters

When you think of something that requires willpower, what's the first thing that comes to mind? For most of us, the classic test of willpower is resisting temptation, whether the temptress is a doughnut, a cigarette, a clearance sale, or a one-night stand. When people say, "I have no willpower," what they usually mean is, "I have trouble saying no when my mouth, stomach, heart, or (fill in your anatomical (解剖的 ˌænəˈtɒmɪk(ə)l) part) wants to say yes." Think of it as "I won't" power.

But saying no is just one part of what willpower is, and what it requires. After all, "Just say no" are the three favourite words of procrastinators (拖延症患者 prəʊˈkræstɪneɪtə(r)) and couch potatoes worldwide. At times, it's more important to say yes. All those things you put off for tomorrow (or forever)? Willpower helps you put them on today's to-do list, even when anxiety, distractions, or a reality TV show marathon threaten to talk you out of it. Think of it as "I will" power—the ability to do what you need to do, even if part of you doesn't want to.

"I will" and "I won't" power are the two sides of self-control, but they alone don't constitute willpower. To say no when you need to say no, and yes when you need to say yes, you need a third power: the ability to remember what you really want. I know, you think that what you really want is the brownie, the third martini, or the day off. But when you're facing temptation, or flirting with procrastination (拖延症 prəˌkræstɪˈneɪʃ(ə)n), you need to remember that what you really want is to fit into your skinny jeans, get the promotion, get out of credit card debt, stay in your marriage, or stay out of jail. Otherwise, what's going to stop you from following your immediate desires? To exert self-control, you need to find your motivation when it matters. This is "I want" power.

Willpower is about harnessing the three powers of I will, I won't, and I want to help you achieve your goals (and stay out of trouble). As we'll see, we human beings are the fortunate recipients of brains that support all of these capacities. In fact, the development of these three powers—I will, I won't, and I want—may define what it means to be human. Before we get down to the dirty business of analyzing why we fail to use these powers, let's begin by appreciating how lucky we are to have them. We'll take a quick peak into the brain to see where the magic happens, and discover how we can train the brain to have more willpower. We'll also take our first look at why willpower can be hard to find, and how to use another uniquely human trait-self-awareness to avoid willpower failure.

Why We Have Willpower

Imagine this: It is 100,000 years ago, and you are a top-of-the-line homo sapiens of the most recently evolved variety. Yes, take a moment to get excited about your opposable thumbs, erect spine, and hyoid bone (which allows you to produce some kind of speech, though I'll be damned if I know what it sounds like). Congratulations, too, on your ability to use fire (without setting yourself on fire), and your skill at carving up buffalo and hippos with your cutting-edge stone tools.

Just a few generations ago, your responsibilities in life would have been so simple: 1. Find dinner. 2. Reproduce. 3. Avoid unexpected encounters with a Crocodylus anthropophagus(that's Latin for "crocodile that snacks on humans"). But you live in a closely knit tribe and depend on other homo sapiens for your survival. That means you have to add "not piss anyone off in the process" to your list of priorities. Communities require cooperation and sharing resources—you can't just take what you want. Stealing someone else's buffalo burger or mate could get you exiled from the group, or even killed. (Remember, other homo sapiens have sharp stone tools, too, and your skin is a lot thinner than a hippo's.)

Moreover, you might need your tribe to care for you if you get sick or injured—no more hunting and gathering for you. Even in the Stone Age, the rules for how to win friends and influence people were likely the same as today's: Cooperate when your neighbor needs shelter, share your dinner even if you're still hungry, and think twice before saying "That loincloth makes you look fat." In other words, a little self-control, please.

It's not just your life that's on the line. The whole tribe's survival depends on your ability to be more selective about whom you fight with (keep it out of the clan) and whom you mate with (not a first cousin, please—you need to increase genetic diversity so that your whole tribe isn't wiped out by one disease). And if you're lucky enough to find a mate, you're now expected to bond for life, not just frolic once behind a bush. Yes, for you, the (almost) modern human, there are all sorts of new ways to get into trouble with the time-tested instincts of appetite, aggression, and sex.

This was just the beginning of the need for what we now call willpower. As (pre)history marched on, the increasing complexity of our social worlds required a matching increase in self-control. The need to fit in, cooperate, and maintain long-term relationships put pressure on our early human brains to develop strategies for self-control. Who we are now is a response to these demands. Our brains caught up, and voilà (那就是 vwɑːˈlɑː) , we have willpower: the ability to control the impulses that helped us become fully human.

Why It Matters Now

Back to modern-day life (you can keep your opposable thumbs, of course, though you may want to put on a little more clothing). Willpower has gone from being the thing that distinguishes us humans from other animals to the thing that distinguishes us from each other. We may all have been born with the capacity for willpower, but some of us use it more than others. People who have better control of their attention, emotions, and actions are better off almost any way you look at it. They are happier and healthier. Their relationships are more satisfying and last longer. They make more money and go further in their careers. They are better able to manage stress, deal with conflict, and overcome adversity. They even live longer.

When pit against other virtues, willpower comes out on top. Self-control is a better predictor of academic success than intelligence (take that, SATs), a stronger determinant of effective leadership than charisma (个人魅力 kəˈrɪzmə) (sorry, Tony Robbins), and more important for marital bliss than empathy (yes, the secret to lasting marriage may be learning how to keep your mouth shut). If we want to improve our lives, willpower is not a bad place to start. To do this, we're going to have to ask a little more of our standard-equipped brains. And so let's start by taking a look at what it is we're working with.

The Neuroscience of I Will, I Won't, And I Want

Our modern powers of self-control are the product of long-ago pressures to be better neighbors, parents, and mates. But how exactly did the human brain catch up? The answer appears to be the development of the prefrontal cortex, a nice chunk of neural real estate right behind your forehead and eyes. For most of evolutionary history, the prefrontal cortex mainly controlled physical movement: walking, running, reaching, pushing—a kind of proto-self-control. As humans evolved, the prefrontal cortex got bigger and better connected to other areas of the brain. It now takes up a larger portion of the human brain than in the brains of other species—one reason you'll never see your dog saving kibble for retirement. As the prefrontal cortex grew, it took on new control functions: controlling what you pay attention to, what you think about, even how you feel. This made it even better at controlling what you do.

Robert Sapolsky, a neurobiologist at Stanford University, has argued that the main job of the modern prefrontal cortex is to bias the brain—and therefore, you—toward doing "the harder thing." When it's easier to stay on the couch, your prefrontal cortex makes you want to get up and exercise. When it's easier to say yes to dessert, your prefrontal cortex remembers the reasons for ordering tea instead. And when it's easier to put that project off until tomorrow, it's your prefrontal cortex that helps you open the file and make progress anyway.

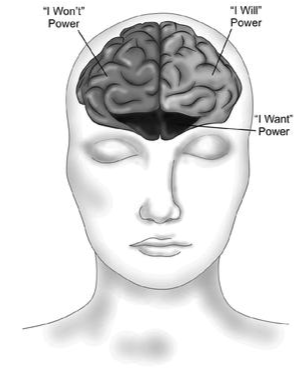

Figure 1. Willpower In The Brain

The prefrontal cortex is not one unified blob of gray matter; it has three key regions that divvy up the jobs of I will, I won't, and I want. One region, near the upper left side of the prefrontal cortex, specializes in "I will" power. It helps you start and stick to boring, difficult, or stressful tasks, like staying on the treadmill when you’d rather hit the shower. The right side, in contrast, handles "I won't" power, holding you back from following every impulse or craving. You can thank this region for the last time you were tempted to read a text message while driving, but kept your eyes on the road instead. Together, these two areas control what you do.