剧本角色

Bohr

男,60岁

这个角色非常的神秘,他的简介遗失在星辰大海~

Heisenberg

男,30岁

这个角色非常的神秘,他的简介遗失在星辰大海~

Margrethe

女,50岁

这个角色非常的神秘,他的简介遗失在星辰大海~

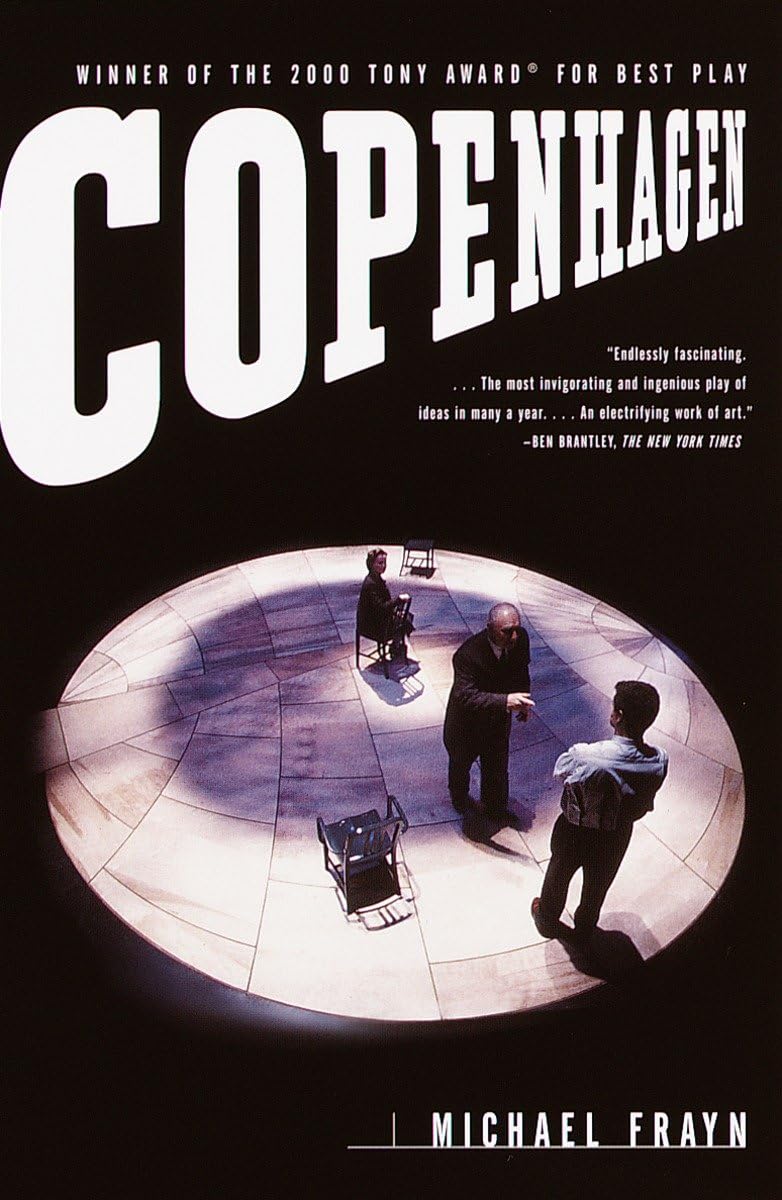

《哥本哈根》是迈克尔·弗雷恩创作的戏剧,基于1941年在哥本哈根发生的一次事件——物理学家尼尔斯·玻尔和他的学生维尔纳·海森堡之间的会面。该剧于1998年在伦敦国家剧院首演,并上演了超过300场

版权归属为迈克尔·弗雷恩,如有侵权,联系作者处理

特别说明:此本涉及很多专业名词,谨慎盲走。

ACT TWO

Heisenberg: It was the very beginning of spring. The first time I came to Copenhagen, in 1924. March: raw, blustery northern weather. But every now and then the sun would come out and leave that first marvellous warmth of the year on your skin. That first breath of returning life.

Bohr: You were twenty-two. So I must have been. . . Thirty-eight.

Bohr: Almost the same age as you were when you came in 1941.

Heisenberg: So what do we do?

Bohr: Put on our boots and rucksacks.

Heisenberg: Take the tram to the end of the line.

Bohr: And start walking!

Heisenberg: Northwards to Elsinore.

Bohr: If you walk you talk.

Heisenberg: Then westwards to Tisvilde.

Bohr: And back by way of Hillered.

Heisenberg: Walking, talking, for a hundred miles.

Bohr: After which we talked more or less non-stop for the next three years.

Heisenberg: We' d split a bottle of wine over dinner in your flat at the Institute.

Bohr: Then I' d come up to your room.

Heisenberg: That terrible little room in the servants' quarters in the attic.

Bohr: And we' d talk on into the small hours.

Heisenberg: How, though?

Bohr: How?

Heisenberg: How did we talk? In Danish?

Bohr: In German, surely.

Heisenberg: I lectured in Danish. I had to give my first colloquium when I' d only been here for ten weeks.

Bohr: I remember it. Your Danish was already excellent.

Heisenberg: No. You did a terrible thing to me. Half-an-hour before it started you said casually, Oh, I think we' ll speak English today.

Bohr: But when you explained. . . ?

Heisenberg: Explain to the Pope? I didn' t dare. That excellent Danish you heard was my first attempt at English.

Bohr: My dear Heisenberg! On our own together, though? My love, do you recall?

Margrethe: What language you spoke when I wasn' t there? You think I had microphones hidden?

Bohr: No, no - but patience, my love, patience!

Margrethe: Patience?

Bohr: You sounded a little sharp.

Margrethe: Not at all.

Bohr: We have to follow the threads right back to the beginning of the maze.

Margrethe: I' m watching every step.

Bohr: You didn' t mind? I hope.

Margrethe: Mind?

Bohr: Being left at home?

Margrethe: While you went off on your hike? Of course not. Why should I have minded? You had to get out of the house. Two new sons arriving on top of each other would be rather a lot for any man to put up with.

Bohr: Two new sons?

Margrethe: Heisenberg.

Bohr: Yes, yes.

Margrethe: And our own son.

Bohr: Aage?

Margrethe: Ernest!

Bohr: 1924 of course .Ernest.

Margrethe: Number five. Yes?

Bohr: Yes, yes, yes. And if it was March, you' re right - he couldn' t have been much more than. . .

Margrethe: One week.

Bohr: One week? One week, yes. And you really didn' t mind?

Margrethe: Not at all. I was pleased you had an excuse to get away. And you always went off hiking with your new assistants. You went off with Kramers, when he arrived in 1916.

Bohr: Yes, when I suppose Christian was still only. . .

Margrethe: One week.

Bohr: Yes. . . . Yes. . . . I almost killed Kramers, you know.

Heisenberg: Not with a cap-pistol?

Bohr: With a mine. On our walk.

Heisenberg: Oh, the mine. Yes, you told me, on ours. Never mind Kramers - you almost killed yourself!

Bohr: A mine washed up in the shallows. . .

Heisenberg: And of course at once they compete to throw stones at it. What were you thinking of?

Bohr: I' ve no idea.

Heisenberg: A touch of Elsinore there, perhaps.

Bohr: Elsinore?

Heisenberg: The darkness inside the human soul.

Bohr: You did something just as idiotic.

Heisenberg: I did?

Bohr: With Dirac in Japan. You climbed a pagoda.

Heisenberg: Oh, the pagoda.

Bohr: Then balanced on the pinnacle. According to Dirac. On one foot. In a high wind. I' m glad I wasn' t there.

Heisenberg: Elsinore, I confess.

Bohr: Elsinore, certainly.

Heisenberg: I was jealous of Kramers, you know.

Bohr: His Eminence. Isn' t that what you called him?

Heisenberg: Because that' s what he was. Your leading cardinal. Your favourite son. Till I arrived on the scene.

Margrethe: He was a wonderful cellist.

Bohr: He was a wonderful everything.

Heisenberg: Far too wonderful.

Margrethe: I liked him.

Heisenberg: I was terrified of him. When I first started at the Institute. I was terrified of all of them. All the boy wonders you had here - they were all so brilliant and accomplished. But Kramers was the heir apparent. All the rest of us had to work in the general study hall. Kramers had the private office next to yours, like the electron on the inmost orbit around the nucleus. And he didn' t think much of my physics. He insisted you could explain everything about the atom by classical mechanics.

Bohr: Well, he was wrong.

Margrethe: And very soon the private office was vacant.

Bohr: And there was another electron on the inmost orbit.

Heisenberg: Yes, and for three years we lived inside the atom.

Bohr: With other electrons on the outer orbits around us all over Europe.

Heisenberg: Mostly Germans.

Bohr: Yes, but Schr?dinger in Zurich, Fermi in Rome.

Heisenberg: Chadwick and Dirac in England.

Bohr: Joliot and de Broglie in Paris.

Heisenberg: Gamow and Landers in Russia.

Bohr: Everyone in and out of each other' s departments.

Heisenberg: Papers and drafts of papers on every international mail-train.

Bohr: You remember when Goudsmit and Uhlenbeck did spin?

Heisenberg: There' s this one last variable in the quantum state of the atom that no one can make sense of. The last hurdle. . .

Bohr: And these two crazy Dutchmen go back to a ridiculous idea that electrons can spin in different ways.

Heisenberg: And of course the first thing that everyone wants to know is, What line is Copenhagen going to take?

Bohr: I' m on my way to Leiden, as it happens.

Heisenberg: And it turns into a papal progress! The train stops on the way at Hamburg.